MAWARU PENGUINDRUM

STATUS

COMPLETE

EPISODES

24

RELEASE

December 23, 2011

LENGTH

24 min

DESCRIPTION

Once you make a decision, does the universe conspire to make it happen? Is destiny a matter of chance, a matter of choice or the complex outcome of thousands of warring strands of fate? All twins Kanba and Shoma know is that when their terminally ill sister Himari collapses at the aquarium, her death is somehow temporarily reversed by the penguin hat that she had asked for. It's a provisional resurrection, however, and it comes at a price: to keep Himari alive they need to find the mysterious Penguin Drum. In order to do that, they must first find the links to a complex interlocking chain of riddles that has wrapped around their entire existence, and unravel the knots that tie them to mystifying diary and a baffling string of strangers and semi-acquaintances who all have their own secrets, agendas and "survival strategies." And in order for Himari to live, someone else's chosen destiny will have to change. It's a story of love, fate, life, death... and Penguins!

(Source: Sentai Filmworks)

CAST

Ringo Oginome

Marie Miyake

Himari Takakura

Miho Arakawa

Shouma Takakura

Ryouhei Kimura

Kanba Takakura

Subaru Kimura

Sanetoshi Watase

Yutaka Koizumi

2-Gou

Ryouhei Kimura

Masako Natsume

Yui Horie

1-Gou

Subaru Kimura

3-Gou

Miho Arakawa

Momoka Oginome

Aki Toyosaki

Yuri Tokikago

Mamiko Noto

Esmeralda

Yui Horie

Keiju Tabuki

Akira Ishida

Hibari Isora

Yui Watanabe

Shirase

Megumi Iwasaki

Hikari Utada

Marie Miyake

Souya

Motoki Takagi

Yousuke Yamashita

Ryousuke Sakamaki

Mario Natsume

Kazusa Aranami

Aoi no Hahaoya

Masami Suzuki

Yukina Kashiwagi

Yoshiko Ikuta

Yui

Rei Matsuzaki

Asami Kuhou

Saori Hayami

Kenzan Takakura

Takehito Koyasu

Sahei Natsume

Hiroshi Ito

EPISODES

Dubbed

Not available on crunchyroll

RELATED TO MAWARU PENGUINDRUM

REVIEWS

pixeldesu

90/100A mystery that pulls you in deeper and deeper every episodeContinue on AniListWell, this certainly was a rollercoaster ride.

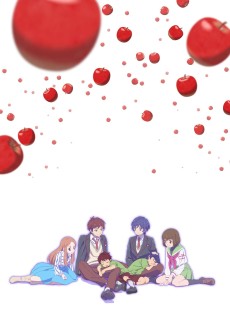

Mawaru Penguindrum centers around the Takakura family, namely the brothers Shouma and Kanba and their sister Himari. One day while visiting the zoo, Himari drops dead, causing dismay for their brothers. A previously bought souvenir however, revives her, and in a dreamlike world, tells the brothers to find the Penguindrum to keep her alive. This is the beginning of an adventure to find said object, and while doing so they encounter various hindrances.

I'm not exactly sure what to write about the story and pacing of Penguindrum. It's mysterious, and every other episode ends with with more questions than before, while uncovering the exact amount of information to keep you hooked and not overly confused (if you can handle the massive intake of information). While the final episodes definitely amplify the amount of questions you'll end up asking yourself, that's probably what will keep you going.

Characters in Penguindrum aside of the Takakura family all play a certain role in the story, receiving attention in short sequences in episodes or sometimes side-arcs uncovering their personality, desires and reasoning for certain actions. Another huge part in personalities are the Takakura brothers and their care for their sister Himari, who is the only family they have left. This feels really authentic, not just in the way they act and talk to her, but also in the actions they are pursuing to keep their sister at their side, creating a feeling of compassion for the viewer towards the Takakura family.

Dialogue and representation of the characters is tied to their personalities, having a wide repertoire of shy and reclusive to very outgoing and direct. Depending on situations, certain characters will go out of character, like a switch being flicked, and their manic self is a suprise to the image they give away usually. Besides that, we are following high school students in their usual lively endeavours, love and past love, conflicts and more.

Visually, Mawaru Penguindrum is an ordinary anime, the style doesn't divert much from usual anime in it's general direction, what's special about it are the details outside of that. Non-relevant characters are displayed as simple and flat boldly-outlined silhouttes. Scenes that are playing in dreams or in the imagination can end up dazing, colorful and vivid, and sometimes scenes just radiate the dark mood they are meant to have with dark base colors and bright red lines and symbols. A lot of the iconography and design of Penguindrum and it's inserts is based on subway/trainline looks, so when characters travel between locations the viewer gets the exact station names shown. The progress through the entirity of the series is also denoted in a subway line, which is visible at the end of the first part of the episode. The several types of penguin illustrations combined with that very simply aesthetic give the series it's own look and flair.

In terms of audio, Penguindrum delivers a solid soundtrack accompanying the different situations our characters will find themselves in. Over the course of the 24 episodes, there will be a multitude of EDs that will sometimes reflect on an episode or foreshadow the mood of the next one coming up, tying us closer to just keep on going. One of the definitive highlights of the show is Triple-H's cover of the song "Rock Over Japan", which is used quite often over the course of the series, and you might just end up humming or singing along when it comes up!

While the huge flood of information, relationships between the characters, details to look for and the general upkeep of the mystery might not be for everyone, I'd definitely recommend Mawaru Penguindrum to the people that have been eyeing to watch it, but beware, it will not make it easy for you to stop once you're in.

Now, there's not much more left for me to say, except for maybe...

SEEEEIZOOON SENRYAKUUUUUUU~

Krankastel

90/100Whimsical but calculated, vibrant yet ominous; Ikuhara's theatrical masterpiece.Continue on AniListIf I were to summarize Ikuhara’s Penguindrum in a single word, it would be __“bold”__. Be it direction, thematic exploration, presentation, it screams being the artistic expression of a man who marches to his own (penguin)drum.

Partially psychological, partially absurdist comedy and partially mystery, but 100% a brain broiler, it is neither orthodox nor easily digestible. Controversial themes are included, and the narrative is not to be taken face-value. I recommend against nitpicking at first watch, opting instead for an empty and open mind intuitively absorbing information.

Episodes are rollercoasters (or rather, trains) alternating or mixing seemingly incongruous elements, such as offbeat comedy, intrapersonal and societal themes, liberal use of plot twists, metaphors:

- Despite not being purely comedic, there is a wide gamut of jokes/gags, some vocal, some visual, some self-standing and some parodies. Those occur even during serious scenes; a bit hit or miss element but also part of Penguindrum's charm.

- Better not spoil too much on themes, but I note those three outside fate and predestination: conformism, repressed desire and “inherited sins”.

- Ikuhara excels at constantly dismantling expectations and presenting new angles to characters or issues. Some narrative tools are abused back and forth, but not haphazardly at all.

- For metaphors, one of the trademarks of Ikuhara’s style, see section [2.].

On characters, stars are the Takakura siblings as well as Ringo Oginome, yet the whole cast is functional within the narrative. Various outlooks on fate are presented depending on each one’s experiences, e.g., more cynical outlooks being juxtaposed against more romantic ones.

__[1. A few words on soundscape]__ Sound quality is all-round good, be it voice acting, music or ambient sounds. Himari’s seiyuu is in my opinion the #1, especially before and during the iconic musical scene, but other voice actors are not far behind, although I believe a couple of voices mismatch their roles (e.g., Kanba’s).

Music is varied, including but obviously not limited to multiple spicy endings, two bittersweet openings and even some classical insert music here and then, such as the Blue Danube. Tracks harmoniously match with respective scenes and/or thematic exploration, and so do ambient sounds. On occasions I also appreciated the lack of background music, that allowed other elements to add their own sound.

__[2. And on Penguindrum's aesthetics]__ Penguindrum thrives on visual storytelling, with images as a narrative tool on their own right. Always keep in mind it is highly symbolical. Be it trains and train lines, the iconic penguins, bird (no, I'm not referring to the penguins) and apple motifs or even the first opening’s title, there is often more than what one only sees. Say penguins: outside providing comic reliefs even during somber scenes, they also serve e.g. as a Ring of Gyges parallel.

Even the presentation of the world follows this philosophy, for scenes can be highly stylistic overall or certain colorful ones can make vivid contrasts with more mundane-looking scenery. Either way, there is much screenshot material to be found, I assure you.

On direction, Ikuhara is influenced by theater, opting for a stage play-like presentation where key details are highlighted whereas secondary ones are minimal.

Other than being economical, this approach allows to pinpoint focus on what truly matters, evident in e.g., extras being represented by signpost figures. There might also be a metaphorical reason behind this approach, but I cannot judge this easily.

All in all, within animation Penguindrum is a highly unconventional work, displaying vision, passion and much technical skill from its staff. Please give it a chance; you might not appreciate it but you will never ever forget it.

Hope you enjoyed my review!

MattSweatshirT

95/100A Postmodernist Examination of FateContinue on AniList

A Postmodernist Examination of Fate

(a lot of this is just impassioned rambling, so it's probably pretty disjointed and doesn’t get all my points across the best–but in a way that fits this series quite well so whatever.)

Throughout my time watching anime, Kunihiko Ikuhara has become one of the directors I am most fascinated by. Stylistically and thematically, he is potentially my single favorite director in the industry; and that all started for me with Penguindrum.

Penguindrum’s immediate disregard for so many conventions and its bombastic style hooked me immediately. By throwing the series’s core ideas in your face but exploring them in such obfuscated, complex ways, it creates an impenetrable sense of mystery and intrigue which it retains for its entire run. Ikuhara’s goofy shoujoesque slap-stick grounds it in a sense of familiarity while the narrative meanders in a space somewhere between incomprehensibility and complete nonsense. And its goofiness is something I personally adore. It never fails to keep me engaged and evoke constant nose laughs. In the interest of not overselling the show and being honest with myself, though, a lot of the actual narrative and characters are pretty straightforward and not all that revolutionary. But the unrelenting Ikuhara style, and the things I feel this piece of media is trying to say that make it something truly special to me. Basically, the reasons I love penguindrum so much are pretty inexplicable and the rest of this review is just my convoluted process of trying to justify it to myself.

Perhaps the thing I enjoy most from a piece of media is the sense that it has something it desperately wants to say. A specific, or even vague line of messaging–a particular set of emotions–or a question that applies to real life. When a work wants to get something across to the viewer that is entirely outside the conventional purposes of simply a well thought out narrative, or a realistic portrayal of characters–that intrigues me. It makes me want to understand not only the general theming or lessons to be learned from it, but all the specificities of its messaging and how it arrives there. Ikuhara is probably both the most fun and most difficult creative to set out to do this for. The chaotic fusion of seemingly endless amounts of symbolism and references make any specificities near-impossible to discern, and only really accessible by way of assumption. Luckily, I'm pretty good at assuming. To a certain extent, I think it's something we do with all stories and art. We experience a piece of media and assume things about what it’s trying to say based on our prior experiences and ways of thinking–and therefore come out with our personal interpretations. Ikuhara’s style of directing and messaging is particularly rich for this kind of thing. Each of his works feels like a mass of disparate threads he gives you an allotted amount of time and context clues to connect together in some sort of way. Penguindrum in my opinion strikes the best balance in his works of being challenging in this respect, but equally rewarding–whereas Utena feels a bit more drawn out and less rewarding–and his newer works being too quick and dense.

Fate is what I would say is the core idea of Penguindrum. As a postmodernist examination of the idea of fate, however, it ends up being about a wide variety of things that can fall under that umbrella. “Fate” means something different to each character in the series, and it can apply to many different concepts throughout its run. Each character's conception of fate serves as a metanarrative–with the ultimate answer to what fate is being an unknowable plurality. What Penguindrum ultimately wants us to consider is the forces that drive us, society, and the world along. What is it that influences, or potentially even controls our motivations and actions? And when confronting these forces, what can one do? When confronting the relative nature of the world and our existence, the postmodern condition, what can one do?

Within this examination of and resignation to the incomprehensibility that is fate and critique of existing systems and ways of doing things that are often taken for granted, is also a more intimate, individual message of inspiration.

Mawaru Penguindrum is an exceedingly inaccessible amalgamation of distinct and at times opposing tones, themes, references, ideas, and decisions made by the staff. It ventures to communicate its ideas not only through the content of the show, but through its form as well.

The show’s production, or form, is exceptionally chaotic and eclectic. Why keep one consistent style when you can express each type of scene depending on its content and tone in an entirely different, unique style. Ringo’s fantasies are portrayed as though they were a fairy tale storybook, while any scene with Sanetoshi becomes significantly more surreal and cryptic. It uses a variety of tones that whiplash from scene to scene and often even conflict with each other in a single scene. It will go from goofy, surreal comedy to stark, intense drama—and in some cases, have intense drama between the characters occurring with goofy comedy from the penguins in the background. The efficacy of this approach is definitely debatable, but it is undoubtedly consistent and intentional in its inconsistency. What Penguindrum aims to communicate with this is the idea that disconnected parts can come together to form one singular whole with meaning. Spinning (mawaru), penguin, and drum are all different, completely irrelevant words to each other. However, in the larger context of the work, they reference some of its themes, while also coming together to form one singular meaning of their own—the title of the show. This idea applies to nearly everything in the show.Here is a fantastic video essay that goes in-depth on penguindrum’s use of these kinds of things:

It all also serves to simulate the postmodern condition, or the world of signs. The incomprehensible whirlwind of information and infinite number of perspectives that exist in the world today. Ikuhara revels in these postmodern sensibilities. With every work, he adamantly advocates for the value of signs and symbols in their meaning and effect on the world.

And so, just as the characters in the series are barraged by the stream of confusing, inexplicable events of the story and forced to consider what they care about in the face of it all, the audience is barraged by a stream of seemingly indecipherable symbols and references and forced to consider the meaning of it all.

__Fate__ Fate, in one sense of the term, is characterized by the inevitable circumstances the characters find themselves in, including their biological family and all of the baggage that comes with that. This is displayed through many examples throughout the show—such as with Yuri’s father being manipulative, telling her to doubt all kindness that doesn’t come from family, as well as physically and sexually abusive. Ringo and her circumstances are the most extensive exploration of this. The tragedy of losing her sister and the poor way her parents handled raising her after the fact caused her to feel bound by her family ties, and thus bound by fate. She embraces a warped idea of this fate, feeling as though she must become Momoka, that leads her to nothing but destructive tendencies. Tons of the side characters exhibit issues as a result of their family–especially women. The patriarchal capitalist framework of our society results in situations like Juri’s, where her grandfather instills toxic ideas into her and her brother, limiting their idea of what fate could be to one that simply follows that framework. Family situations such as these are juxtaposed by the Takakuras, a family of three siblings who are all unrelated biologically but have a more genuine connection on the basis of love than any of the families created on the basis of coincidentally, or fatedly, being related.

“The world is divided into the chosen and the unchosen”.

Some children are chosen and loved by their biological families. Others are not. However, none of the children had any choice of their own when it came to being born into such a circumstance. Therefore, the essentialization of traditional familial ties creates a toxic conformity which results in vastly negative outcomes for the unchosen. The existence of these family ties is one of the forces that influences our motivations and actions–as well as tradition in general. Essentialization, or a lack of plurality in one’s consideration leads to a skewed perception of the world which can normalize negative forces and ostracize positive ones.

This critique on the essentialization of family ties in favor of other, potentially more real connections is not where Penguindrum’s social commentary ends. The very same juxtaposed examples of family circumstances and connections, when related to other aspects of the show, take on a broader meaning and become a critique of Japanese capitalist society at large. These other aspects of the show we must view in relation to this mostly pertain to the Kiga group and Sanetoshi. The Kiga group are a direct representation of the real life “AUM” cult terrorist group in Japan who were behind the tragic 1995 Tokyo gas attacks. Haruki Murakami, a japanese author who is referenced throughout the show, wrote a book called "Underground" which is a collection of interviews with victims of the gas attack. It highlights the shock this atrocity incurred onto society, however at the end of the book Murakami stops talking about the atrocity, and starts discussing the AUM group themself. He outlines their motivations and analyzes how it is the toxic nature of society that has caused these ostracized people to be pushed so far. While the Kiga group and Sanetoshi by the end of Penguindrum are essentially the final antagonists and are quite explicitly bad people, along the way we get to learn their motivations. Their griefs about society include the unfair reality of the chosen and the unchosen. They say that the world is cold and toxically conformative. And we as the audience have seen plenty of evidence to support their claims in the form of the afore-mentioned examples of family situations. The Kiga group, however, are not only referring to family situations, but to society as a whole, and Penguindrum gives us no reason to question the validity of this, only reason to oppose their methods of enacting this change through terrorism. Evidence of their griefs also materialize with the “Child Broiler”, which retains the relation to family situations, but takes form as an industrialized assembly-line machine which treats humans as objects—directly comparable to many critiques of how capitalism treats the worker as a replaceable object, part of the industrialized machine of society. When unchosen or not profitable for the system, you are simply disposed of. This conformity of the workers, particularly present in Japanese society, strips away individuality, as depicted by all of the background characters in the show being the same outlined figures. This is juxtaposed by the bright, incredibly individualistic character designs of our main characters who are apart from the conformity of the biological family.

A lot of life is about finding your identity in the face of the vast number of negative forces such as these that affect you. Exclusionary systems and the internalizing of false dichotomies and other preconceptions can limit our view of what we could be–What society could be.

Although, in another sense of the term, “fate” is used to validate the meaning of characters’ lives despite the struggles they face. This takes form in instances such as Momoka having always listened to Tabuki’s piano playing and loving him despite him thinking his life was meaningless without the talent to play like his brother. This is also seen in Yuri’s circumstances, where Momoka thinks she is beautiful and loves her despite Yuri’s internalization that she is ugly and love can only come from family. Momoka can be seen as a representation of the good of fate—as it is said by Tabuki and Yuri, she made them ‘see everything in the world as beautiful’. This ever-present possibility for beauty is something that is obfuscated by the various toxic influences over our lives. When confronting those negative influences, you can finally see that possibility for beauty within everything, but attempting to grasp it is to disregard the rest of reality–it’s impossible. Momoka is someone who transcends fate, her existence is beauty itself–and therefore the cruel reality of fate takes her away.

The entirely negative view of fate Sanetoshi and the Kiga group have, as well as the entirely positive view of fate Momoka has, are modernist ideologies. Narratives that claim to be concrete in their perspective on the world. These ideologies take root as ideas in our society–creating movements within different groups of people that they get a hold on. Ideas and ideologies such as this are like ghosts, as the show displays, affecting reality in ethereal, permeating ways. In some instances they can be empowering, providing inspiration and a level of validation to people’s lives–but they can be just as equally dangerous, giving justifications to terrorist organizations.

Ultimately, the idea of fate is postmodernist conception; concrete only in its uncertainty. The incomprehensible amount of factors, or disparate parts, that come together to form the cause of our reality—on an individual, societal, and worldwide scale. It is essentially the human condition. Everyone goes on throughout their lives discovering and dealing with the infinite amount of forces that affect them. We inherit this life with an existentially lost world moving along around us, not giving any consideration to our confusion or existence. We must either come to terms with or reject the negative influences that we inherit, and hold on to what really matters to us. The struggle against fate is a desperate, endless process full of unanswerable questions we are forced to answer anyway. This can also be seen as “God”, an incomprehensible entity in control, which Penguindrum references multiple times as being cruel, because reality is cruel. Fate also encompasses all of the good, though, as Momoka helps people see. This is what the Kiga group and Sanetoshi have lost sight of as a result of being disillusioned to the normalized cruel society they are in. Penguindrum’s own perspective on fate lies in the middle of these two oppositions. It accepts fate as an existence, instead of trying to destroy it like Kiga and Sanetoshi, but is also deeply skeptical of it. It displays how fate can lead to the normalization of negative forces, and argues that we should strive to change those things. A sympathy is displayed for the kiga group on an individual scale, but not for their actions. Reality as it exists is indeed a result of the incomprehensible amount of factors in the world that create what we see through cause and effect, but those factors are in our hands.

On an intimate, individual scale, the answer Penguindrum offers is love. Instead of destruction to overcome the cruelty of fate, one must turn to sacrificial love to aid in the alleviation of the suffering life brings onto us. This love must be sacrificial in the sense that your connections with others must be genuine to the point where you are willing to share each other’s pain. As Shouma hugs Ringo while she is on fire at the end of the show to take the pain onto him. As the eponymous penguindrum within the show is shared by the chosen Kanba with the unchosen Shouma, and by the now partly chosen Shouma with the unchosen Himari, that all leads to the formation of their mismatched family which gives their lives meaning through the genuine connection of disparate parts. The answer to escape the unfair fate on an individual scale for the unchosen, is to choose each other. However, as Penguindrum shows, this is ultimately not enough. In episode 20, as Shouma and Himari “choose” the unchosen stray kitten, society takes it away. The show then ends on a beautifully tragic note in episode 24. The penguindrum is eventually returned to Kanba as a whole, as fate forces it to be—however he sacrifices himself yet again. His and Shouma’s sacrifices result in the transfer of fate to a reality in which they—Shouma, Kanba, Himari, and Ringo—all live but aren’t together as a whole anymore. Fate, working at a larger scale than the individual, has stripped it away from them. But their love transcends it all, as Himari finds a note from them expressing their love for her from across fate lines and cries, unknowing as to exactly why.ends it all, as Himari finds a note from them expressing their love for her from across fate lines and cries, unknowing as to exactly why.

What I probably like most in media is the tackling of identity and the tackling of societal issues and sociological phenomena. Better yet, the tackling of what it means to grapple with one's identity in the face of societal issues and how various sociological phenomena affect that. Penguindrum explores this extensively, down to the biggest, most daunting questions of it all. It concludes without any final answer for the issues it highlights. It ends as a postmodernist examination, an analyzation of the structures of reality, or fate, we find ourselves in—and posits that we should be aware of and question any such structures, but any answers to such an issue that pertains to the entirety of reality are contingent to their own perspectives and will never be objective or impartial. The chosen are partial to society as it benefits them, and the unchosen such as the Kiga group are partial to their view of fate which ignores the good. We ultimately live in an incomprehensible, relative world that we cannot find any objective meaning in. The society we live in subjects us to conformity and the essentialization of that which is normalized, ostracizing the abnormal.

However, as ikuhara often does, he ends it with a final message of inspiration. Maybe this is really all this fucking show was about in the first place and ive just been rambling trying to justify my feelings toward it. But, what is the point of art if not to inspire and affect in positive ways in spite of anything else. After a harshly realistic depiction of the world, societies, and identity, it leaves us with one final hope. The only hope perhaps that the unchosen are left with; the establishment of genuine connections and love with others, which transcends fate itself. Love for the sake of itself, which is perhaps the only thing untainted by the negative forces around us. A pure form of expression afforded to us in this tragic existence.

---

SIMILAR ANIMES YOU MAY LIKE

ANIME DramaYuri Kuma Arashi

ANIME DramaYuri Kuma Arashi ANIME ActionKyousougiga (TV)

ANIME ActionKyousougiga (TV) ANIME ComedySarazanmai

ANIME ComedySarazanmai ANIME ComedyBakemonogatari

ANIME ComedyBakemonogatari ANIME ActionZetsuen no Tempest

ANIME ActionZetsuen no Tempest ANIME ActionFlip Flappers

ANIME ActionFlip Flappers

SCORE

- (3.95/5)

MORE INFO

Ended inDecember 23, 2011

Main Studio Brain's Base

Trending Level 1

Favorited by 3,348 Users

Hashtag #PENGUINDRUM